The Nature of Freemasonry

When speaking of the nature of Freemasonry, most people may think it is a religious organization, since its constitution borrows stories from the Bible to illustrate its principles.

In fact, according to the official information published by the United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE), Freemasonry is one of the world’s oldest and largest non-religious, non-political fraternal charitable organizations.

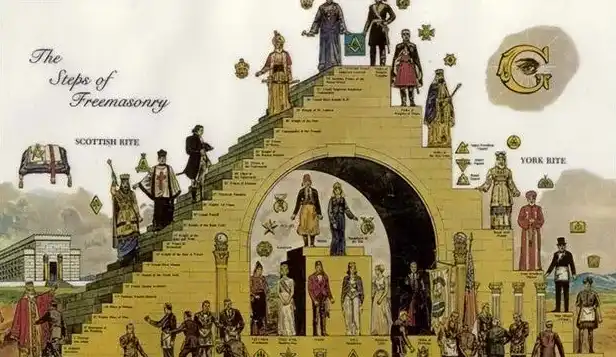

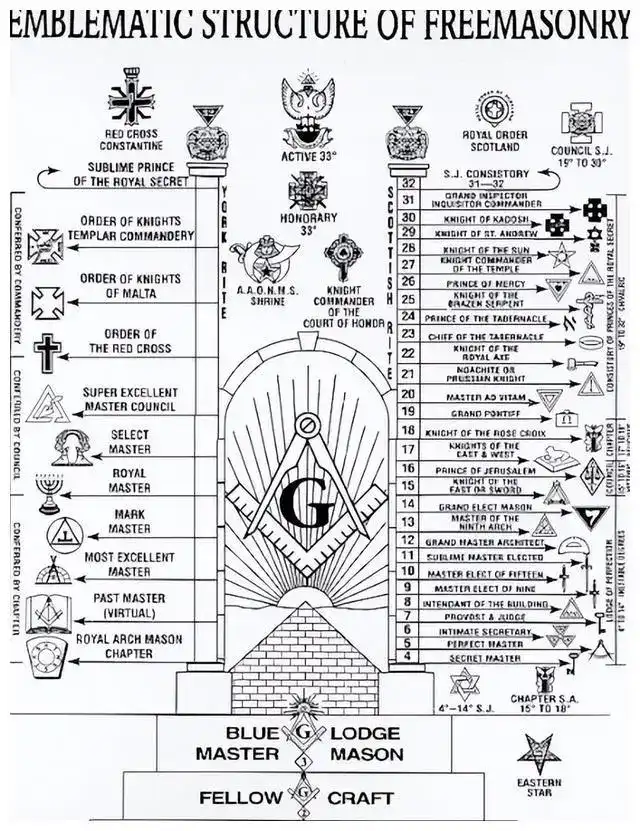

Early Freemasonry was mainly composed of craftsmen, but gradually expanded to include people from all walks of life. Its members included merchants, architects, soldiers, actors, royalty, and politicians. While its origins and rituals were influenced by Christianity, membership was not restricted to Christians.

One of the requirements for entry reflects this:

“You must profess a belief in a Supreme Being (for example, in God or another deity — but Freemasonry is not tied to Christianity or any other religion, and many Masonic lodges even encourage polytheistic beliefs).”

Thus, while belief in some form of deity was required, membership was not limited to followers of a single faith. Freemasonry is not a church, but it does contain many religious elements. Its lodges often carry names such as St. John’s Lodge or St. Andrew’s Lodge. Its teachings emphasize morality, charity, and obedience to the law. The American scholar Blackstock described Freemasonry as “a moral order, devised by wise men, built upon tolerance, brotherhood, and benevolence.”

Through a series of ritual activities, Freemasonry instills ethical values in its members, promoting unity, friendship, honesty, and fairness. Its core principle is widely known: “to make a good man better.” This ideal urges members to display virtues in all aspects of life — diligence at work, self-restraint in daily conduct, mutual respect, and willingness to help others.

The Origins of Freemasonry in British North America

In 1620, the Mayflower brought a group of English Puritans to North America. Forced to start a new life in an unfamiliar land, these settlers — and the immigrants who followed — gradually developed complex feelings toward their mother country: resentment of British oppression mixed with deep admiration for British culture.

Before the formation of the first Grand Lodge in London (1717), Freemasonry had already spread to the American colonies from Britain. The earliest recorded Mason in America was John Skene, a member of the Old Aberdeen Lodge in Scotland. He immigrated to New Jersey in 1682 and served as Deputy Governor until his death in 1690. The influx of British immigrants and trade helped establish Masonic lodges across the colonies.

Different colonies later claimed the honor of having America’s oldest lodge. In Pennsylvania, Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette documented early lodges. In Georgia, James Oglethorpe — founder of the colony and a Mason since 1732 — established Solomon’s Lodge in Savannah in 1734, still regarded as the oldest continuously operating lodge in the United States.

In 1730, Daniel Coxe was appointed by the Duke of Norfolk as Provincial Grand Master for New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. In 1733, Henry Price was commissioned in London as Grand Master of North America and authorized the founding of St. John’s Lodge in Boston — the first officially chartered Masonic lodge in the colonies. That same year, Benjamin Franklin became a Mason; by 1734, he published Anderson’s Constitutions of the Free-Masons in Philadelphia, the first Masonic book printed in America, spreading Masonic ideas widely.

Both “Ancients” and “Moderns” lodges took root across the colonies. By the eve of the Revolution, dozens of lodges had been founded in New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. These lodges fostered networks of trust and solidarity that later proved crucial during the independence movement.

The Key Role of Freemasonry in the American Revolution

Looking at the course of the Revolution, Freemasonry contributed in three major ways:

- The Spirit of Brotherhood and Mutual Aid

Masonic ideals of fraternity and solidarity united members in resisting British rule.

Paul Revere, a Mason, famously risked his life to deliver intelligence to fellow patriots. George Washington, also a Mason, embodied the fraternity’s ideals of virtue and perseverance as he rallied the colonies. - Loyalty and Responsibility

Loyalty was a core Masonic value — loyalty not just to the lodge, but to shared principles of liberty. Leaders such as John Hancock and Joseph Warren demonstrated unwavering dedication to independence. By contrast, Benedict Arnold’s betrayal was condemned not only as treason to his country but also as a betrayal of his Masonic brethren. Washington, when nominated to be Grand Master of Virginia lodges, declined the honor so he could devote himself entirely to the cause of independence — a testament to his sense of responsibility. - Military Lodges

During the war, traveling “military lodges” were established within the Continental Army, the most famous being the American Union Lodge (1776). Many of its members were officers who played vital roles in the war. These lodges fostered unity among soldiers from different colonies, boosted morale at Valley Forge with social gatherings, and provided aid to the wounded, prisoners, and bereaved families.

Such activities strengthened trust, reinforced the spirit of sacrifice, and helped sustain the revolutionary cause until ultimate victory.