In the long years before Einstein proposed special relativity, Newtonian classical mechanics was like the “Bible” of the physics world, dominating humanity’s understanding of the universe’s laws. In that era, speed and time were two concepts strictly separated, independent of each other and unrelated. In the public’s ingrained perception, speed was a physical quantity describing the rapidity of an object’s motion, while time was a constant scale measuring the sequence of events—speed was speed, time was time, clearly distinct, with no possibility of mutual influence.

If someone at the end of the 19th century told a physicist, “An object’s speed of motion will change the rate at which time passes,” they would most likely be regarded as talking nonsense, or even considered mentally unstable. Even today, in this era of highly advanced technology, when we popularize this idea to people without a physics background, many still shake their heads in doubt, feeling that Einstein’s theory back then was simply “wishful thinking.”

This perception of separating speed and time originates from the “absolute spacetime view” upon which Newtonian classical mechanics relies. This view is the cornerstone of classical mechanics, supporting the entire edifice of classical physics, and it deeply aligns with people’s everyday experiences, thus remaining unshaken for centuries.

Understanding the Absolute Spacetime View in Newtonian Mechanics

So, what is the “absolute spacetime view”? In The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, Newton explicitly stated: Time is absolute and flows uniformly, independent of any external things; space is also absolute and eternally unchanging, serving as the absolute framework for the motion of objects. Simply put, in any corner of the universe, whether in an Earth laboratory or near a distant star, the rate of time’s passage is exactly the same; spatial scales do not change due to the motion of objects.

The reason the absolute spacetime view took root so deeply lies in its high alignment with our daily life experiences. On Earth, whether at the equator or the poles, whether sitting still or running and jumping, the time we feel passing is consistent—a day is 24 hours, an hour is 60 minutes, a minute is 60 seconds, without any deviation.

Of course, from a strict physics perspective, the rate of time’s passage does vary extremely slightly at different locations on Earth, related to the distribution of Earth’s gravitational field, but this difference is so small that it cannot be perceived by everyday clocks; only high-precision atomic clocks can measure it, and this was a discovery made after the birth of relativity. In the classical mechanics era, people were completely unaware of this subtle difference.

At the end of the 19th century, the physics community ushered in what seemed like a “perfect” era. Through the efforts of generations of physicists, the theoretical system of classical mechanics had become quite complete, accurately explaining everything from celestial motions to the movements of objects on the ground. Newton’s law of universal gravitation successfully predicted the existence of Neptune, pushing the authority of classical mechanics to its peak. At the same time, the development of thermodynamics and statistical physics provided a clear understanding of the nature of thermal phenomena; the birth of Maxwell’s equations unified electricity, magnetism, and light, constructing a complete theoretical system of electromagnetism.

In this context, physicists of the time generally fell into an optimistic, even arrogant, mood. They believed that the edifice of physics had basically been built, and the remaining work was just some minor repairs and supplements to this building, such as correcting deviations in experimental data and perfecting theoretical derivations in details. The famous physicist Lord Kelvin said in a speech in 1900: “The future of physics will only be found in the sixth decimal place.” In their view, humanity had already touched the ultimate truth of physics, and what remained was only the finishing touches of refinement.

However, Lord Kelvin also mentioned a dissonant note in this speech: “There are two small clouds floating in the sky of physics now.” No one expected that these two seemingly insignificant “clouds” would ultimately trigger a physics revolution, completely overturning the “perfect” edifice of physics in people’s minds. These two “clouds”—one was the contradiction between the Michelson-Morley experiment and the “ether” hypothesis, and the other was the conflict between blackbody radiation experiments and classical mechanics theory. And it was precisely the first “cloud” that directly gave birth to the emergence of special relativity, breaking the rule of absolute spacetime; the second “cloud” then nurtured quantum mechanics, opening the door to the exploration of the microscopic world. Today, we will focus on the story of the first “cloud”—how it evolved from what seemed like a minor contradiction into a “storm” that subverted classical physics.

The Ether Hypothesis: Reconciling Newtonian Mechanics and Maxwell’s Equations

To understand the contradiction between the Michelson-Morley experiment and the “ether” hypothesis, we must first clarify a core issue: What exactly is “ether”? Why was this concept proposed? In fact, the birth of “ether” was essentially an assumption made by physicists at the time to reconcile the profound contradiction between Newtonian classical mechanics and Maxwell’s equations. These two theories were both core pillars of classical physics, yet they harbored an incompatibility that left physicists in a dilemma.

Let us first outline the core views of the two theories separately.

The core foundation of Newtonian classical mechanics is the absolute spacetime view, and a key conclusion derived from the absolute spacetime view is: “The speed of any object’s motion is relative and must be determined by choosing an appropriate reference frame.” This view is easy to understand; we can frequently sense it in daily life. For example, when we say a car’s speed is 100 km/h, the default reference frame is the ground; if this car is side by side with another car traveling at 80 km/h in the same direction, then to the people in the second car, the first car’s speed is only 20 km/h. Another example: When we walk on a moving train at 5 km/h relative to the train, our speed relative to the ground is the train’s speed plus our walking speed (if walking in the same direction). This law of velocity addition in classical mechanics is called the “Galilean transformation,” which fully conforms to our everyday experience and has been verified by countless experiments.

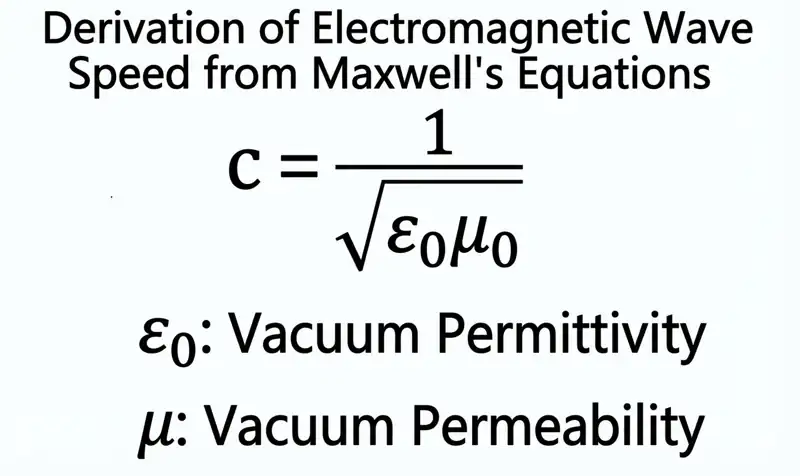

However, the appearance of Maxwell’s equations dealt a heavy blow to this view of “velocity relativity.” Maxwell’s equations were one of the pinnacle achievements of 19th-century physics; they unified the basic laws of electric and magnetic fields and successfully predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves, also proving that light is a type of electromagnetic wave. The form of this equation set is extremely concise and elegant, praised by physicists as “the formulas written by God.” But it was this seemingly perfect equation set that contained a conclusion incompatible with classical mechanics: The speed of light is a constant that does not depend on the choice of reference frame and only depends on the vacuum’s magnetic permeability and dielectric constant.

In other words, no matter which reference frame you choose to measure the speed of light, the result is the same, approximately 300,000 km/s.

This conclusion seemed utterly absurd at the time. According to classical mechanics’ velocity addition rule, if we emit a beam of light forward from a car traveling at 100 km/h, the speed of this beam of light relative to the ground should be the speed of light plus the car’s speed, that is, 300,000 km/h + 100 km/h. But according to Maxwell’s equations, the speed of this beam of light relative to the ground is still 300,000 km/s, and the car’s travel speed has no effect on the speed of light. This created a sharp contradiction: Either Newtonian classical mechanics is wrong, or Maxwell’s equations are wrong.

But both theories have been verified by countless experiments, making it hard to believe that either one is incorrect. Newtonian classical mechanics has ruled the physics world for over 300 years, accurately explaining all mechanical phenomena from apples falling to planetary revolutions, and its authority has long been deeply rooted. Maxwell’s equations have also passed experimental tests; the existence of electromagnetic waves has been confirmed by Hertz’s experiments, and light’s electromagnetic nature has been widely recognized. Faced with two “correct” yet mutually contradictory theories, physicists fell into confusion. Unwilling to abandon either theory, they began attempting various assumptions to reconcile the conflict between them. The “ether” hypothesis was born in this context.

At the time, physicists proposed that the universe is filled with a special substance that is invisible, intangible, colorless, and odorless; this substance was named “ether.” They believed that “ether” is absolutely stationary and is the only “absolute reference frame” in the universe, and that the speed of light is relative to the “ether.” In other words, the constant speed of light mentioned in Maxwell’s equations actually refers to the speed of light relative to the “ether” being constant at 300,000 km/s; and according to classical mechanics’ velocity addition rule, when measuring the speed of light in different reference frames, since these reference frames have different speeds relative to the “ether,” the measured speeds of light should also differ. In this way, the contradiction between Newtonian classical mechanics and Maxwell’s equations seemed to be perfectly reconciled by the “ether” hypothesis.

From the logic of scientific research, proposing an assumption is not a problem in itself. In fact, many great scientific theories started as assumptions, such as Copernicus’s “heliocentric theory,” which was initially just an assumption and was later confirmed through a series of observational experiments. Whether an assumption is reasonable depends on whether it can be experimentally verified, whether it can explain existing physical phenomena, and whether it can predict new physical phenomena. After the “ether” hypothesis was proposed, although it temporarily reconciled the contradiction between the two theories, it was still just an assumption and needed to be proven through experiments. Thus, searching for “ether” and verifying the “ether” hypothesis became an important research direction in the physics community at the time.

Among the many experiments searching for “ether,” the most famous and crucial one is the Michelson-Morley experiment.

The Michelson-Morley Experiment: Challenging the Ether Hypothesis and Light Speed Invariance

This experiment was jointly designed and completed by American physicists Albert Michelson and Edward Morley, with the purpose of proving the existence of “ether” by measuring differences in the speed of light in different directions and calculating the speed of Earth’s motion relative to “ether.” Next, we briefly outline the design ideas and process of this experiment.

According to the “ether” hypothesis, “ether” fills the entire universe and is absolutely stationary. Earth orbits the sun at about 30 km/s, so during its orbit, Earth moves relative to “ether,” and this relative motion produces an “ether wind”—just like when we run in windless weather, we feel the air blowing against us. If the “ether wind” exists, then when light propagates in the direction of the “ether wind,” its measured speed should be the speed of light minus Earth’s speed relative to “ether”; when light propagates perpendicular to the “ether wind,” its measured speed should be the square root of the speed of light squared minus Earth’s motion speed squared; when light propagates in the direction opposite to the “ether wind,” its measured speed should be the speed of light plus Earth’s motion speed. By measuring differences in the speed of light in different directions, the existence of the “ether” wind can be proven, thereby proving the existence of “ether.”

To accurately measure this extremely small difference in the speed of light, Michelson designed a special instrument—the Michelson interferometer. The core principle of this instrument is: Split a beam of light into two beams, one propagating parallel to Earth’s orbital direction, the other perpendicular to Earth’s orbital direction; after the two beams travel a certain distance, they reflect back and recombine; if there is a difference in the propagation speeds of the two beams, interference fringes will appear when they recombine; by observing changes in the interference fringes, differences in the speed of light can be determined. Michelson and Morley conducted this experiment in 1887. To improve the precision of the experiment, they also placed the experimental device on a stone slab floating on mercury, which minimized the impact of ground vibrations on the experiment and allowed the experimental device to be easily rotated to measure the speed of light in different directions.

Before the experiment began, Michelson and Morley were full of confidence, believing they would definitely observe changes in the interference fringes, thereby proving the existence of “ether.” However, the result of the experiment greatly disappointed them—no obvious changes in interference fringes were observed, no matter how they rotated the experimental device, no matter what time of day or season of the year the experiment was conducted. This meant that the speed of light in different directions was completely the same, with no differences. In other words, the “ether wind” did not exist, and the substance “ether” likely did not exist either.

This experimental result was like a bombshell, causing an uproar in the physics community. The precision of the Michelson-Morley experiment was very high, sufficient to detect theoretically existing differences in the speed of light, so the experimental result was credible. But this result completely contradicted the “ether” hypothesis and also conflicted with classical mechanics’ velocity addition rule. Faced with this “anomalous” experimental result, physicists fell into great confusion. The mainstream view at the time believed that “ether” absolutely existed, and the reason the Michelson-Morley experiment did not observe the expected result must be due to some factors not considered in the experiment. Thus, many physicists began proposing various supplementary assumptions to explain the contradiction between the experimental result and the “ether” hypothesis.

Among them, the most famous supplementary assumption is the “Lorentz contraction hypothesis.”

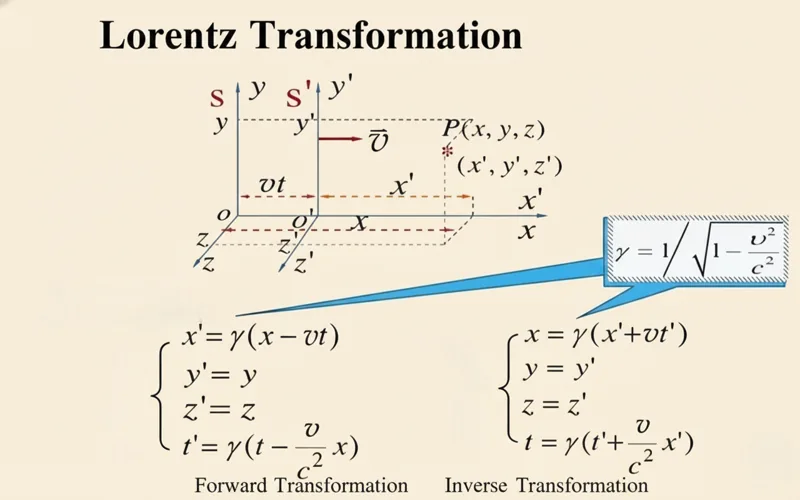

Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz proposed that objects undergo a slight length contraction in the direction of motion relative to “ether,” and the degree of this contraction is related to the object’s speed of motion. According to this hypothesis, the path length of the beam of light propagating in the direction of Earth’s orbit in the Michelson interferometer would become shorter due to the length contraction of the instrument, exactly offsetting the difference in speed of light caused by the “ether wind,” so no changes in interference fringes were observed in the experiment. To quantify this contraction effect, Lorentz also derived the corresponding mathematical formula—the Lorentz transformation.

In addition, some physicists proposed the “ether drag hypothesis,” arguing that Earth drags the surrounding “ether” along with it, so near Earth’s surface, “ether” is stationary relative to Earth, and thus no “ether wind” is produced, so no difference in speed of light is observed in the experiment.

But these supplementary assumptions all had a common problem: They were specially proposed to accommodate the “ether” hypothesis and lacked independent experimental evidence. Moreover, these assumptions made the “ether” hypothesis increasingly complex—for the sake of maintaining an initial assumption, new assumptions had to be continuously added, which is not an ideal state in scientific research, like having to fabricate more lies to cover one initial lie. More importantly, these supplementary assumptions did not fundamentally resolve the contradiction between classical mechanics and Maxwell’s equations; they only temporarily masked the contradiction.

In the decades following the Michelson-Morley experiment, more and more physicists repeated similar experiments, and the precision of the experiments also increased, but all experiments yielded results consistent with the Michelson-Morley experiment: The speed of light is constant in any reference frame, with no differences. This forced physicists to re-examine their own perceptions—could “ether” really not exist? Could Newton’s absolute spacetime view really be wrong?

Just as the entire physics community was sinking into a state of profound confusion and bewilderment…, a young physicist stepped forward. With a subversive way of thinking, he completely resolved the contradiction between classical mechanics and Maxwell’s equations and thoroughly broke the rule of absolute spacetime. This physicist was Albert Einstein. At the time, Einstein was only 26 years old, working at the Swiss Bern Patent Office, not a professional physicist, but with his profound thinking on physical laws and bold questioning, he proposed a great theory that could change humanity’s worldview—special relativity.

Einstein’s Special Relativity: Two Basic Principles and the Lorentz Transformation

Einstein did not, like other physicists, try to maintain the “ether” hypothesis and absolute spacetime view by adding new assumptions. Instead, he keenly realized that the key to the problem might not lie in the experiment itself, but in our basic understanding of spacetime. He proposed that since all experiments prove that the speed of light is constant and independent of the reference frame, we should directly accept this experimental fact and build a new theoretical system on the basis of taking “the invariance of the speed of light” as a basic principle. And the “ether” hypothesis itself was an assumption proposed to reconcile contradictions; now that this assumption contradicts experimental facts, the simplest and most reasonable approach is to directly discard the “ether” hypothesis—this is exactly the embodiment of Occam’s razor principle: “Entities should not be multiplied unnecessarily,” that is, when explaining a phenomenon, a theory that can use fewer assumptions is more reliable than one that requires more assumptions.

Thus, in 1905, Einstein published the paper On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies, formally proposing special relativity. The core foundation of this paper is two basic principles: The first is the “principle of the constancy of the speed of light,” that is, the speed of light in vacuum is constant in any inertial reference frame and is independent of the relative motion of the light source and observer; the second is the “principle of relativity,” that is, physical laws are equivalent in any inertial reference frame, and there is no special inertial reference frame. These two principles seem simple but contain subversive ideas, directly overthrowing Newton’s absolute spacetime view.

Let us first delve into these two basic principles.

The Two Basic Principles of Special Relativity Explained

- Einstein’s Principle of Relativity Physical laws are the same in all inertial reference frames.

- Principle of the Constancy of the Speed of Light In all inertial frames, the speed of light in vacuum is the same, independent of the relative motion between inertial frames, and also independent of the motion of the light source and observer.

The “principle of relativity” was not first proposed by Einstein; Galileo had long proposed a similar “Galilean principle of relativity,” that is, mechanical laws are equivalent in any inertial reference frame. Einstein expanded the scope of this principle to the entire physics, including electromagnetic laws. This means that not only can mechanical experiments not distinguish between different inertial reference frames, but electromagnetic experiments also cannot distinguish them—there is no absolute, special inertial reference frame, which fundamentally negates the meaning of “ether” as an absolute reference frame.

The “principle of the constancy of the speed of light” is the core of special relativity and the most subversive principle to everyday experience. This principle directly accepts the result of the Michelson-Morley experiment, clearly stating that the speed of light is independent of the reference frame. This means that the “Galilean transformation” in classical mechanics is wrong and needs to be replaced by a new transformation rule—this is the Lorentz transformation. It should be noted that although Lorentz had long derived the Lorentz transformation, he did not realize the profound physical meaning of this transformation and only used it as a mathematical tool to explain the contradiction in the “ether” hypothesis. Einstein, through the “principle of the constancy of the speed of light” and the “principle of relativity,” strictly derived the Lorentz transformation theoretically and gave it a completely new physical connotation: The Lorentz transformation reveals the intrinsic connection between time and space, proving that time and space are not absolute but relative, changing with the speed of the object’s motion.

With the introduction of the Lorentz transformation, a series of magical inferences of special relativity were born, among which the most famous are the time dilation effect, length contraction effect, mass increase effect, and the well-known mass-energy equation E=mc². These inferences completely changed our understanding of time, space, mass, and energy, constructing a brand new relative spacetime view.

Let us first look at the time dilation effect.

Time Dilation in Special Relativity: Why High Speeds Slow Down Time

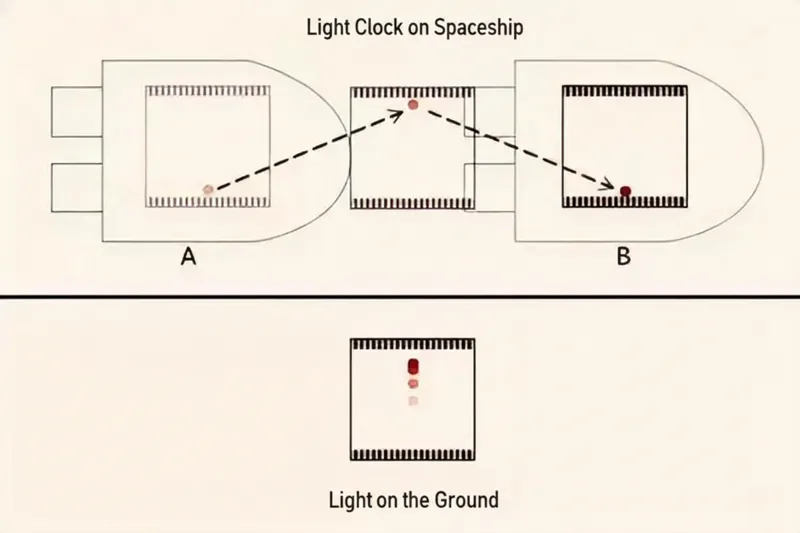

The core conclusion of this effect is: Moving clocks run slow; the faster the object’s speed of motion, the slower the rate of time’s passage; when the object’s speed approaches the speed of light infinitely, time will tend to stop. Why does this phenomenon occur? Actually, the root lies in the principle of the constancy of the speed of light. We can understand it through a simple thought experiment: Suppose there is a stationary clock composed of a light source and a receiver; the light source emits a beam of light vertically upward, and the light reaches the upper mirror and reflects back to the receiver; this process is one unit of time.

Now, let this clock move at a certain constant speed. Then, to the stationary observer, the path of light’s propagation becomes a diagonal line—the light emitted by the light source needs to travel along the diagonal to the mirror and then reflect back along the diagonal to the receiver. Since the speed of light is constant, the length of the diagonal is longer than the vertical distance, so to the stationary observer, the time required for the clock to complete one unit of time becomes longer, that is, the clock runs slow.

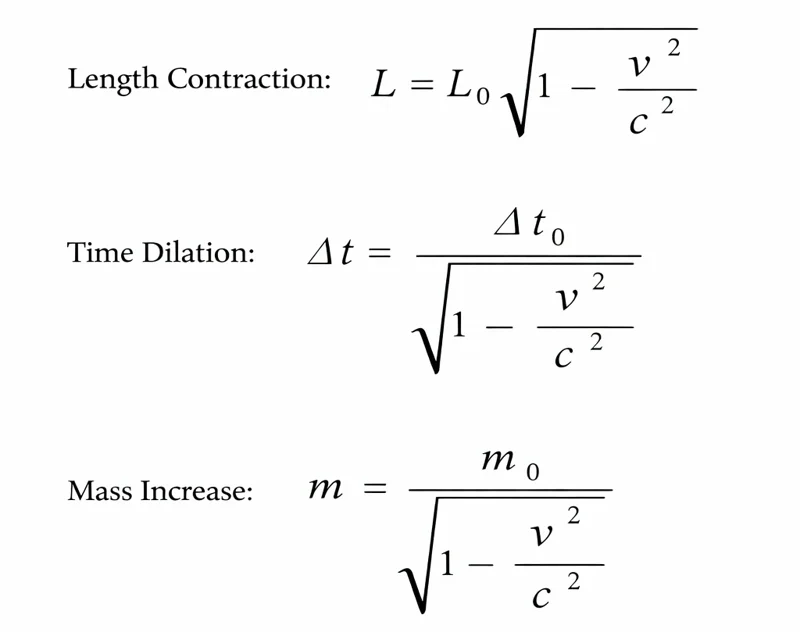

The mathematical expression for the time dilation effect is: Δt = Δt₀ / √(1 – v²/c²), where Δt is the time measured by the stationary observer, Δt₀ is the time in the moving object itself (called proper time), v is the object’s speed of motion, and c is the speed of light. From the formula, it can be clearly seen that when v=0, Δt=Δt₀, time passes normally; as v increases gradually, the value of √(1 – v²/c²) decreases gradually, the value of Δt increases gradually, and time’s passage slows down; when v approaches c infinitely, √(1 – v²/c²) approaches 0 infinitely, and Δt approaches infinity, and time tends to stop.

It needs to be emphasized that the time dilation effect is not a subjective perception, nor is it a malfunction of the clock itself, but an attribute of time itself—the time of a moving object does indeed slow down. This effect has been confirmed by countless experiments, such as the global flight experiment with high-precision atomic clocks: Two completely synchronized atomic clocks, one placed on the ground and one on a high-speed flying airplane; after the airplane flies for a period of time, the atomic clock on the airplane is found to be slightly slower than the one on the ground, and this difference matches exactly with the theoretical calculation of the time dilation effect.

Accompanying the time dilation effect is the length contraction effect. The core conclusion of the length contraction effect is: The length of a moving object in the direction of its motion will shorten; the faster the object’s speed of motion, the more obvious the length contraction; when the object’s speed of motion approaches the speed of light infinitely, the length will tend to zero.

The mathematical expression for the length contraction effect is: L = L₀ × √(1 – v²/c²), where L is the length of the object measured by the stationary observer, L₀ is the length of the object at rest (called proper length), v is the object’s speed of motion, and c is the speed of light. From the formula, it can be seen that when v=0, L=L₀, the length is normal; as v increases gradually, L decreases gradually, and the length contracts; when v approaches c infinitely, L approaches 0 infinitely. Similarly, the length contraction effect is also an attribute of space itself, not the object being “compressed,” but the spatial scale in the moving reference frame changing.

In addition to the relativization of time and space, special relativity also revealed the relationship between mass and speed, that is, the mass increase effect. The core conclusion of the mass increase effect is: The mass of a moving object will increase with the increase in speed; when the object’s speed of motion approaches the speed of light infinitely, the mass will tend to infinity.

The mathematical expression for the mass increase effect is: m = m₀ / √(1 – v²/c²), where m is the mass of the moving object, m₀ is the object’s mass at rest (called rest mass), v is the object’s speed of motion, and c is the speed of light. This effect means that to continuously increase an object’s speed, the force applied must also continuously increase because the mass is continuously increasing; when the object’s speed approaches the speed of light, the mass tends to infinity, requiring infinite force to increase the speed even a little more, so any object with non-zero rest mass cannot reach the speed of light; the speed of light is the limit of motion speed for objects in the universe.

E=mc² and Other Relativistic Effects: Mass-Energy Equivalence in Special Relativity

One of the greatest contributions of special relativity is unifying mass and energy, proposing the famous mass-energy equation E=mc². This equation indicates that mass and energy can be converted into each other; a certain mass corresponds to a certain energy, and changes in energy will also cause changes in mass. The appearance of the mass-energy equation completely changed people’s understanding of mass and energy, laying the theoretical foundation for the development and utilization of nuclear energy—for example, the explosion of an atomic bomb utilizes the principle of mass loss converting into huge energy during nuclear fission; nuclear power plants generate electricity based on the energy released from nuclear fission. At the same time, the mass-energy equation also explains why stars can continuously emit light and heat—the nuclear fusion reaction inside stars converts hydrogen atomic nuclei into helium atomic nuclei, and during this process, there is mass loss; the lost mass is converted into huge energy, released in the form of light and heat.

Returning to our initial question: What is the relationship between speed and time? In Newton’s absolute spacetime view, speed and time are mutually independent; but in Einstein’s relative spacetime view, speed and time are closely linked—the speed will change the rate of time’s passage, and the measurement of time also depends on the choice of reference frame. The root of this connection lies in the principle of the constancy of the speed of light: To ensure that the speed of light is constant in any reference frame, time and space must be relative and must change with changes in the reference frame.

Here, a common misunderstanding needs to be clarified: Many people think that “the speed of light is constant” refers to the propagation speed of light being unchanged, but in fact, the essence of the speed of light is an intrinsic property of four-dimensional spacetime. In special relativity, the speed of light is not just the speed of light but the propagation speed of all particles with zero rest mass and also the maximum speed of information transmission. For example, the propagation speed of gravitational waves and gluons is the speed of light. In other words, the speed of light is a fundamental constant of the universe; it defines the structure of spacetime and also determines the transmission of causality—any influence of events cannot propagate at a speed exceeding the speed of light, otherwise it would violate the causality law.

Addressing Doubts: Why Special Relativity’s Assumptions Hold Up Against Experiments

Although special relativity’s theoretical system is very rigorous, the derivation process is completely logical, and it has been verified by more and more experiments, even today, many people still question it. The main reason is that many inferences of special relativity contradict our everyday experiences, and the choice of reference frame easily leads to confusion.

For example, some people raise such a question: “If A moves at high speed relative to B, then to B, A’s time slows down; but to A, B is also moving at high speed, so A would think B’s time slows down. Are both statements correct?” The answer is yes, because the measurement of time is relative; different reference frames have different time standards. As long as we specify the reference frame, we can accurately judge the passage of time. And when the two reference frames meet again, since at least one of them has undergone acceleration and deceleration processes (no longer an inertial reference frame), the final time difference can be judged through general relativity; this is also the solution to the “twin paradox.”

Another very important point to emphasize is that the principle of the constancy of the speed of light is an assumption. As we mentioned repeatedly earlier, the foundation of special relativity is two basic principles, and these two principles are essentially assumptions. This point confuses many people: Since it’s an assumption, why should we believe it? In fact, the essence of scientific theory is a “logical system based on assumptions”; whether a scientific theory is credible does not lie in whether its assumptions are “intuitive,” but in whether it can explain existing experimental phenomena, whether it can accurately predict new experimental results, and whether it can withstand the test of time.

The “ether” hypothesis was also an assumption, but this assumption was ultimately proven wrong by experiments because it could not explain the result of the Michelson-Morley experiment and could not accurately predict other experimental phenomena. While the principle of the constancy of the speed of light is also an assumption, it can perfectly explain the contradiction between classical mechanics and Maxwell’s equations, can accurately predict a series of phenomena such as time dilation, length contraction, and mass increase, and these predictions have all been verified by experiments. For example, in particle accelerators, the lifetimes of high-speed moving particles become longer, which is the manifestation of the time dilation effect; cosmic ray muons can reach the ground because the high-speed motion of muons causes time to slow down, thereby extending their lifetimes.

In addition, the normal operation of mobile phone navigation systems also relies on corrections from special relativity—satellites orbiting Earth at high speeds produce the time dilation effect, causing the clocks on satellites to be out of sync with ground clocks; if not corrected, the navigation error would become larger and larger.

More importantly, the assumptions of special relativity are very concise—merely through two basic principles, a complete theoretical system is constructed that can explain a wide range of physical phenomena. In contrast, to maintain the “ether” hypothesis, physicists had to continuously add various supplementary assumptions, making the theory increasingly complex, which also violates the principle of simplicity in scientific research. As Einstein said: “What is real in physics must be simple logically.” The simplicity of special relativity also gives it stronger persuasiveness.

Of course, we have every right to question special relativity and can propose our own assumptions to construct new theories. But as we said earlier, any new theory must satisfy one condition: It must be superior to special relativity, able to explain all phenomena that special relativity can explain, able to solve problems that special relativity cannot solve, and able to be verified by experiments. To date, no theory has been able to achieve this. Special relativity has been born for over a hundred years, and in these hundred-plus years, it has undergone the test of countless experiments; whether it is the motion of particles in the microscopic world or the motion of celestial bodies in the macroscopic world, all prove the correctness of special relativity. It has become one of the cornerstones of modern physics, together with quantum mechanics, building our basic understanding of the universe.

Further Reading:If All Sunlight Hit One Person: Earth’s Doomsday Rhapsody