Imagine this: your friend’s spaceship slips too close to a black hole and begins to fall inward.

From a distance, what would you see?

Common sense says the answer is obvious. Gravity grows stronger, so the ship should fall faster and faster.

But with black holes, reality is never that simple.

To understand why, we need to rewind more than three centuries—back to a man hiding from a plague.

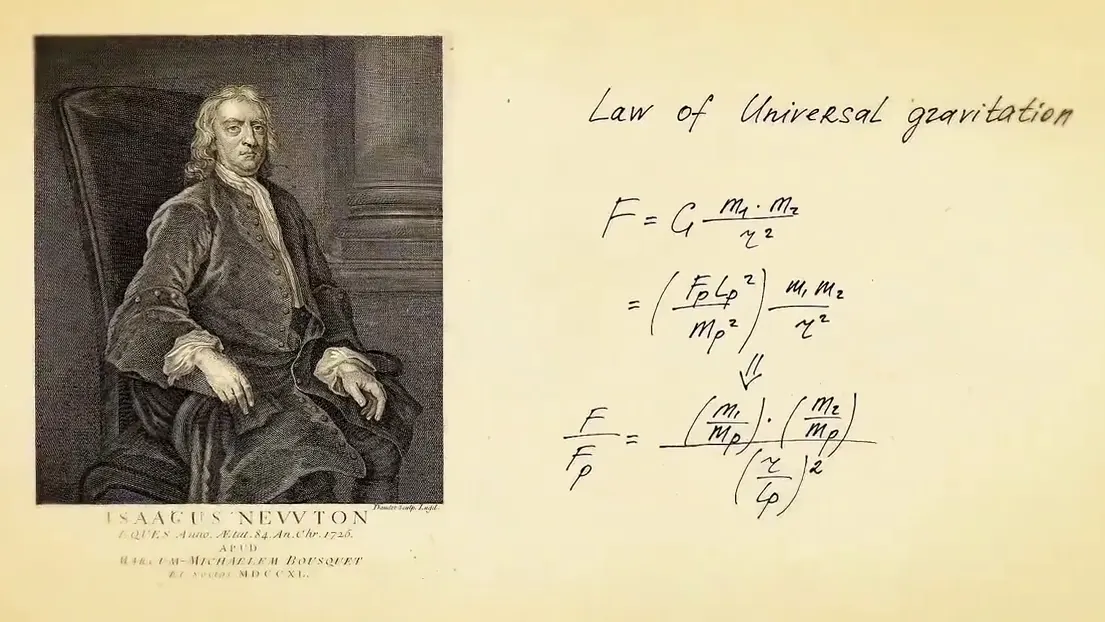

Newton’s Question: Why Do Things Fall Down?

In 1666, Isaac Newton retreated to the countryside to escape the Great Plague. Cut off from society and formal work, he began thinking about a deceptively simple question:

Why do apples fall downward instead of flying up into the sky?

By 1687, his answer took the form of Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, where he introduced the law of universal gravitation. With a single elegant formula, Newton explained how every object with mass attracts every other object in the universe.

It was a triumph of human thought—one equation describing the motion of planets, falling apples, and everything in between.

And yet, Newton himself was deeply uneasy.

How could two objects, separated by vast empty space, influence each other instantly, without any medium connecting them?

He openly admitted his discomfort:

That one body may act upon another at a distance through a vacuum, without the mediation of anything else, is to me so great an absurdity that I believe no man who has in philosophical matters a competent faculty of thinking can ever fall into it.

Gravity worked. But why it worked remained a mystery.

Einstein’s Elevator and the Birth of Curved Spacetime

More than 200 years later, a 30-year-old Albert Einstein found a radically different answer.

In his famous “elevator thought experiment,” Einstein realized that gravity is not a force pulling objects together across empty space. Instead, massive objects warp spacetime itself, and other objects simply follow the curved paths laid out before them.

In 1915, this insight became the theory of general relativity.

At its heart lies the Einstein field equation. On one side: the distribution of mass and energy. On the other: the curvature of spacetime they create. The equation looks deceptively compact—but hidden inside are ten coupled, nonlinear partial differential equations, making exact solutions extraordinarily difficult.

Which is why what happened next surprised everyone.

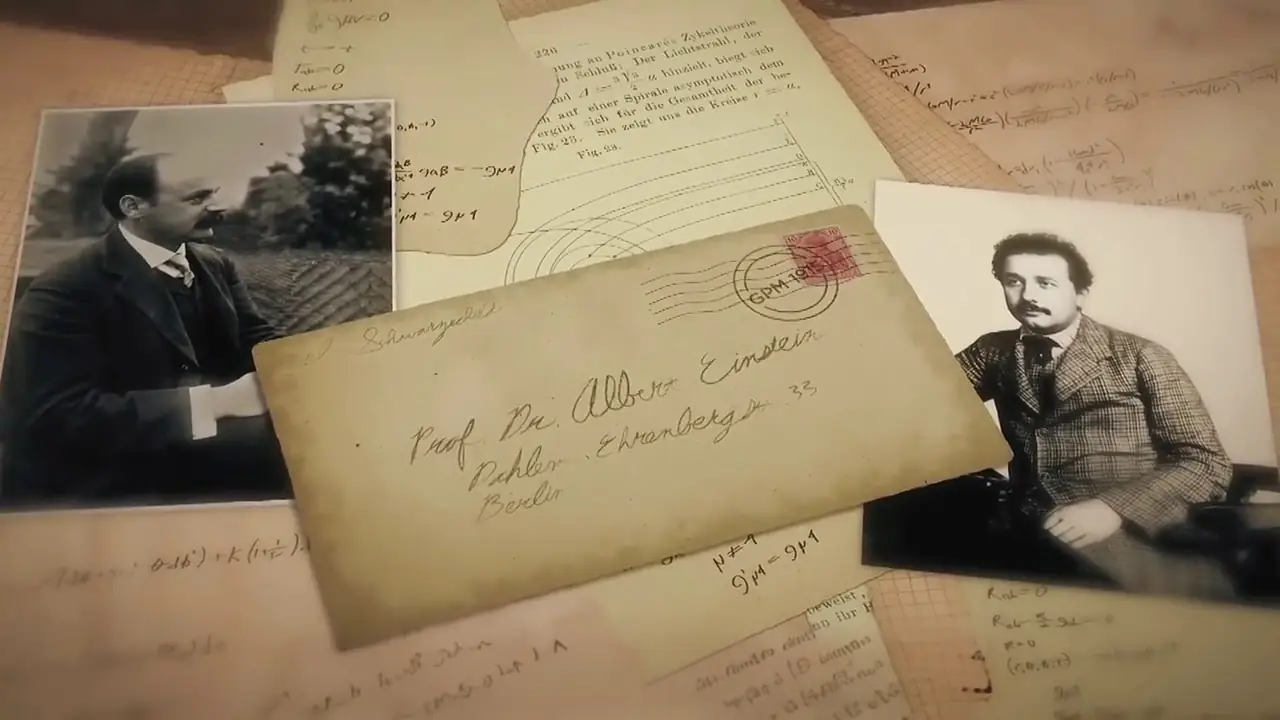

A Letter from the Battlefield

Less than a month after Einstein published general relativity, he received a letter from the front lines of World War I.

The sender was Karl Schwarzschild, a German astrophysicist who, while calculating artillery trajectories for the army, had also solved Einstein’s equations exactly—for the simplest possible case: a static, uncharged, perfectly spherical mass.

This solution, now known as the Schwarzschild solution, revealed something astonishing.

If an object is compressed within a certain radius—now called the Schwarzschild radius—its escape velocity exceeds the speed of light. Nothing, not even light itself, can escape once it crosses this boundary.

Decades later, physicist John Wheeler would give such objects a name:

Black holes.

The boundary itself became known as the event horizon.

The Two Paradoxes of the Schwarzschild Black Hole

At first glance, the Schwarzschild solution seems clean and elegant. But it hides two profound problems.

1. Mathematical infinities

At the Schwarzschild radius, certain quantities blow up to infinity. In physics, infinities are usually a warning sign—something has gone wrong, or at least something is being misinterpreted.

2. Time appears to stop

As an object approaches the event horizon, the time coordinate in Schwarzschild’s equations slows down and eventually reaches zero.

Because this time coordinate corresponds to the clock of a distant observer, it suggests something bizarre: from the outside, an object never actually crosses the event horizon. It appears to freeze in place forever.

This leads to the famous frozen star paradox and was one of the reasons Einstein himself doubted that black holes could exist in reality.

Why Spacetime Diagrams Can Mislead Us

To make sense of this, physicists often turn to spacetime diagrams.

Imagine lighting a lamp above your head. Light spreads outward in all directions, forming an expanding sphere. Because nothing can transmit information faster than light, everything you can ever influence lies within that sphere.

If we remove two spatial dimensions and plot space against time, that sphere becomes a light cone. The edges of the cone—set at 45 degrees—represent the path of light.

In flat spacetime, this picture works beautifully. Distances and intervals behave nicely. But spacetime diagrams are projections—and projections always lose information.

Just as no flat map can perfectly represent the surface of the Earth, no 2D diagram can fully capture the geometry of curved 4D spacetime.

In Schwarzschild coordinates, spacetime near the event horizon is “compressed” in such a way that creates the illusion of infinite time delay. The curvature itself, however, does not diverge there.

The infinity is not physical. It’s a coordinate artifact.

Change the coordinates, and it disappears.

Falling In vs. Watching From Afar

This distinction is crucial.

For the falling object itself, nothing special happens at the event horizon. It crosses the boundary in a finite amount of proper time, completely unaware of anything unusual.

But for a distant observer, the story looks very different.

To understand why, consider a powerful visualization: the waterfall model.

Spacetime as a Waterfall

In this model, space itself flows toward the black hole like water pouring over a cliff.

The grid represents space. The flow represents how spacetime is curved not only in space, but in time.

Objects—and even light—move through space the way boats move through water. Light’s speed is constant relative to space, just as a boat’s speed is constant relative to the river.

As you approach the event horizon, the inward flow of space accelerates. Light trying to escape upstream finds it harder and harder to make progress. The signals it sends take longer and longer to reach an outside observer.

At the event horizon, the inward flow reaches the speed of light.

From that point on, all paths lead inward.

No signal emitted beyond this boundary can ever escape.

What You Actually See

So what would you see if your friend fell into a black hole?

You would never witness the full fall.

Instead, you’d see their spaceship slow down as it approaches the event horizon. Its movements would become increasingly sluggish. The light it emits would stretch to longer wavelengths, shifting toward red and fading into darkness.

Eventually, the image would appear frozen—dimmed, reddened, and vanishing into the black.

Not because your friend stopped moving—but because the information can no longer reach you.

Beyond the Simplest Black Hole

Of course, Schwarzschild black holes are idealized. Real black holes rotate, and rotating (Kerr) black holes are far stranger.

They possess ergospheres, frame dragging, and spacetime geometries so exotic that, mathematically, they even allow hypothetical bridges to other regions of spacetime.

Whether those bridges are real is another question entirely.

A Door, Not an Ending

Black holes are not merely cosmic vacuum cleaners or frozen prisons of time.

They challenge our intuition about space, time, and causality itself.

From Newton’s discomfort with action at a distance, to Einstein’s curved spacetime, to Schwarzschild’s wartime equations—each step has pushed human understanding further beyond common sense.

We once thought black holes were the end of everything.

But the deeper we look, the more they resemble something else entirely:

A door.

As Einstein famously said:

The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.

We cannot fully capture Earth on a flat map, and we cannot fully understand black holes from a single coordinate system.

The universe does not obey our intuition.

It simply is what it is.

Further Reading: Event Horizon Telescope Achieves Another Milestone? A Color Photograph of a Black Hole