On October 7, 2025, the Karolinska Institute in Sweden announced that this year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to three scientists—two from the United States and one from Japan—for their pioneering work on peripheral immune tolerance. Their research solved a fundamental question in immunology: how does the immune system distinguish between “self” and “non-self”? Beyond answering this century-old puzzle, their discoveries have profoundly reshaped our understanding of autoimmune diseases, organ transplantation, and cancer immunotherapy.

The Immune System: A Double-Edged Sword

Our bodies are constantly exposed to billions of bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms. Without a robust immune system, even minor infections could be fatal. For example, patients with HIV/AIDS do not die from the virus itself, but from the inability to defend against common infections—a mild cold could become life-threatening.

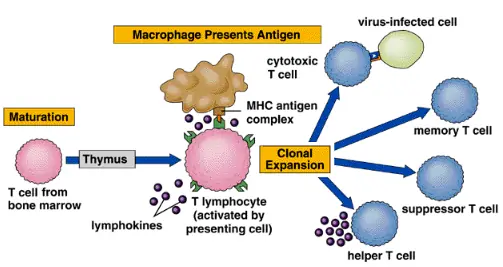

Among the various immune cells, T cells serve as the body’s elite forces. They precisely identify and eliminate infected or abnormal cells. However, a critical question arises: how do T cells know who the enemy is and who belongs to the body?

If T cells misidentify the body’s own tissues as foreign invaders, autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes can develop—akin to a military turning against its own nation.

Traditional Understanding: The Thymus as a “Training Ground”

For decades, scientists believed that T cells acquire the ability to distinguish self from non-self primarily in the thymus. T cells originate in the bone marrow and then migrate to the thymus, where they undergo rigorous “training” processes known as positive and negative selection:

- Positive selection retains T cells capable of recognizing self-MHC molecules, ensuring basic immune functionality.

- Negative selection eliminates T cells that react too strongly to self-antigens, preventing attacks on healthy tissues.

While elegant, this system is not foolproof. Some “rogue” T cells escape thymic selection and reach peripheral tissues, posing a potential threat. The question then arises: how does the body control these escapees to prevent autoimmune disaster?

This brings us to the key concept behind this year’s Nobel Prize: peripheral immune tolerance.

Breakthrough Discovery: Regulatory T Cells and the Immune “Brake”

Japanese immunologist Shimon Sakaguchi, a student of Nobel laureate Tasuku Honjo, made a landmark contribution to this problem.

In the 1990s, Sakaguchi conducted a highly creative experiment: he removed the thymus from mice, theoretically leaving them unable to undergo central T cell tolerance, which should have resulted in severe autoimmune disease. Yet when healthy T cells were introduced into these “thymus-less” mice, something remarkable happened—the mice recovered.

Further analysis revealed a special subset of T cells expressing CD25 on their surface. Unlike conventional T cells, these cells do not attack self-tissues. Instead, they actively suppress the overactivation of other T cells, acting as the immune system’s “police” or “brake system.” These cells were named regulatory T cells (Tregs).

This discovery revolutionized immunology. Even when thymic selection fails, the body possesses a peripheral backup system: Tregs patrol tissues and suppress self-reactive T cells, maintaining immune balance.

The Genetic Key: FOXP3 as the Identity Code for Tregs

How are Tregs generated, and what determines their identity? Two American scientists provided crucial answers.

Studying a mouse model with severe autoimmune disease, characterized by widespread skin lesions, organ damage, and shortened lifespan, they performed large-scale genetic screening. Among hundreds of thousands of gene candidates on the X chromosome, they identified a critical mutation in the FOXP3 gene.

Mutations in FOXP3 prevent proper development or function of Tregs, eliminating peripheral tolerance and leading to multi-organ autoimmunity. Humans exhibit a similar genetic disorder: IPEX syndrome (Immune dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked), caused by FOXP3 defects.

FOXP3 is now recognized as the “master regulator” of Treg cells, providing a genetic blueprint for the immune system’s regulatory capacity. This discovery opened an entirely new avenue for immunology research.

From Basic Science to Clinical Revolution: Harnessing Tregs

The work of these three scientists, while grounded in basic immunology, has profound clinical implications. Treg cells enable two major therapeutic strategies:

1. Enhancing Treg Function: Organ Transplantation and Autoimmune Disease

- In organ transplantation, rejection occurs when the recipient’s immune system attacks donor tissue. By boosting Treg numbers or function, rejection can be suppressed, reducing dependence on immunosuppressive drugs.

- In autoimmune diseases, augmenting Tregs or activating their pathways may provide long-term solutions, treating the underlying cause rather than just symptoms.

2. Suppressing Treg Function: Cancer Immunotherapy

- Tumors exploit Treg-mediated suppression to create an “immune-privileged” environment, evading immune detection.

- Temporarily inhibiting or depleting Tregs around tumors can release the “brakes,” allowing cytotoxic T cells to attack aggressively—a principle increasingly applied in checkpoint inhibitor therapies.

Why This Work Deserves the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prize recognizes not only exceptional achievements but also transformative insights that create entire new fields of study. These scientists established the theoretical framework of peripheral immune tolerance and uncovered Tregs as a critical regulatory system—essentially digging a deep well in the immunology landscape that has attracted countless researchers.

Today, Treg research is a cornerstone of immunology, oncology, and transplantation medicine, with thousands of publications and numerous ongoing clinical trials worldwide.

Conclusion: Honoring the Power of Basic Science

The 2025 Nobel Prize celebrates decades of persistent, meticulous work in basic science. While no “miracle cure” emerged overnight, these discoveries provide a key to understanding one of life’s most intricate balances: immune tolerance.

From thymic selection to peripheral regulation, from CD25 to FOXP3, from a single sick mouse to transformative therapies, this work exemplifies the essence of science: uncovering microscopic truths that illuminate the future of human health.

As for tomorrow’s Nobel in Physics—perhaps it will go to the “grandfather of AI,” Alan Turing. But today, the Medicine Prize reminds us: true breakthroughs often start with a simple question—

“How do we avoid attacking ourselves?”

And the answer is far more elegant, subtle, and beautiful than we ever imagined.