Does purple really exist? From the purple hues in a sunset sky to the violets in a flower shop or the purple emojis on your phone screen, we’ve all encountered it. But ask a physicist, and they might just shrug and say, “Sorry, it’s not in the spectrum.” This isn’t science fiction—it’s the reality of color perception. Don’t worry; I’ll break it down step by step, blending in the latest scientific experiments to make it both fun and factual. Let’s get started!

First, Let’s Unpack the “Behind-the-Scenes” of Color

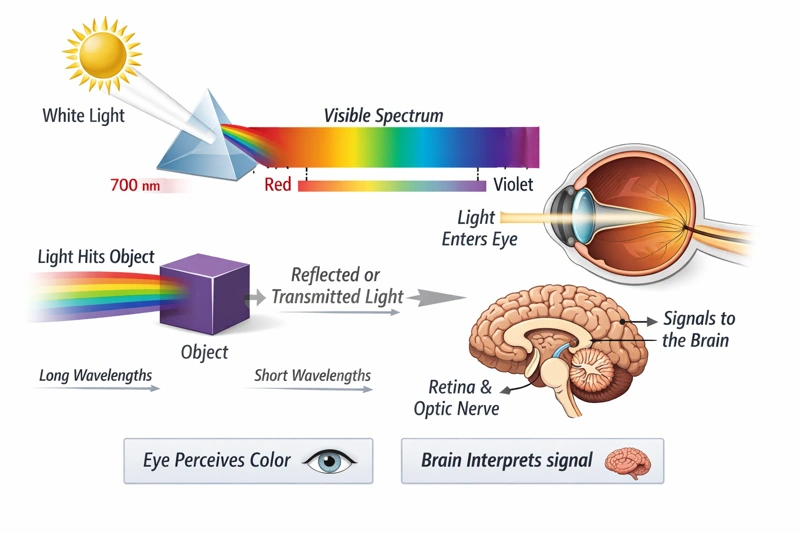

To understand purple, we need to start from the basics. Color isn’t an inherent property of objects—it’s the result of an interaction between light, our eyes, and our brain. Sunlight (or any white light) is a mix of electromagnetic waves, with the visible spectrum ranging from long-wave red (about 700 nanometers) to the short-wave edge of violet (about 400 nanometers). When light hits an object, the reflected or transmitted parts enter our eyes.

Our eyes contain three types of cone cells, like three “light sensors”: L-type (sensitive to red), M-type (green), and S-type (blue). They capture signals from different wavelengths and send them to the brain’s visual cortex. The brain then acts like a master mixer, blending these signals to create the colors we know. For example, orange is a harmonious blend of red and green, with a corresponding mixed wavelength. But purple? It plays a “non-spectral” trick.

In simple terms, the visible spectrum is a straight line from red to blue (or the violet end), but purple isn’t on that line. It requires a “marriage” of red and blue light—no single wavelength can activate both L-type and S-type cones while ignoring the M-type. This leaves the brain scratching its head: signals from both ends firing at once, with the middle silent? So, it invents a “patch”: purple. This isn’t a glitch; it’s an evolutionary smart move to handle complex light environments.

Scientific Experiments: How the Brain “Fakes” Purple

Sounds like philosophical musing? No—neuroscientists have proven it with experiments. As early as the 20th century, psychophysicists discovered through “metamerism” experiments that the same color perception can come from different spectral combinations. But recent brain imaging tech has made the truth crystal clear.

Take a 2025 optical illusion experiment: Researchers designed a scene where purple elements only appear at the fixation point, while the periphery looks gray-blue. When eyes fixate, the brain’s V4 area (responsible for color processing) “reconstructs” the signals, forcing purple perception; but shift your gaze, and it vanishes instantly. This shows purple relies on attention and distance—the brain isn’t a passive receiver but an active “filler.” The experiment used fMRI to scan over 20 participants, revealing that synchronized activation of S-type and L-type cells triggers extra neural circuits, simulating a “non-existent” wavelength.

Another direct 2025 study used spectrometers and EEG monitoring: Subjects were exposed to pure red + blue mixed light, and the brain’s color mapping area (in the occipital lobe) “bent” the spectrum, inserting a virtual “purple wheel” to bridge the red-blue gap. Participants consistently reported it as unique—not as “cool” as blue or “warm” as red, but a one-of-a-kind “hybrid.” These experiments aren’t limited to humans—even fruit fly models show similar “pseudo-purple” responses to multi-channel stimuli, suggesting it’s an ancient biological mechanism.

Fun fact: The experiments also exposed purple’s “fragility.” Interfering with S-type cells (like with a blue-light filter) degrades purple into pink or gray. It reminds us: Color is a subjective “consensus,” not an objective fact.

Everyday Life: Purple’s “Master of Disguise”

So, where does our daily purple come from? It’s everywhere, hiding in tech and nature’s tricks.

The most relatable example: Household LED lights. Those glowing “purple bulbs” are actually red-blue diode combos—red at about 630 nm, blue at 460 nm. The eyes catch the dual signals, the brain stirs, and voilà—purple is born. Try snapping a photo with your phone camera (which is more spectrum-faithful), and you’ll see the purple shift to bluish or reddish. Another classic: Purple pixels on screens. In RGB systems, purple is full R (red) and B (blue), with G (green) off—pure digital-era “brain fill-in.”

In nature? Purple grapes or violet petals look dreamy, but it’s molecular sleight-of-hand. They absorb green-yellow light (500-600 nm) and reflect red + blue. Under sunlight, this mixed reflection fools your cones, cueing the brain’s “purple magic.” From an evolutionary view, it might help plants camouflage or attract pollinators—who says illusions can’t be practical?

Historical Echoes: From Newton to the Royal Purple Robe

Purple’s tale isn’t just science; it’s woven into human culture. In 1666, Isaac Newton used a prism to split white light, yielding a continuous spectrum: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. He insisted on seven colors to match the musical scale, romanticizing the sacred number 7. But the truth? The spectrum gradients seamlessly, with “indigo” just a blue-violet transition—Newton’s “artistic tweak.”

The ancients were even craftier. In the Roman Empire, Tyrian purple dye came from Mediterranean sea snails—one gram cost as much as a slave’s yearly wage. Dyeing a single robe could feed a family for over a decade! Reserved for emperors, it symbolized supreme power. Chemically, it’s an oxidized indole compound with red-blue fluorescence—a “fake purple” at heart. In the Byzantine era, purple robes became emblems of authority, influencing art and fashion to this day.

Not the Same for Everyone: Purple’s “Personal Customization”

Don’t assume purple is a universal standard. Each brain’s color palette varies slightly due to genetics and experience. Colorblind folks show it starkly: Red-green colorblindness (affecting 8% of men globally) lacks L/M cells, turning purple “blue-gray”; blue-yellow (rare) weakens S cells, blurring purple and blue, stripping the world of nuance.

The animal kingdom takes it further. Dogs have only two cone types (yellow-blue), with weak red signals, so purple light registers as pure blue—explaining why your pup ignores that purple toy. Hummingbirds flip it: They discern ultraviolet “pseudo-purples” for foraging. These differences highlight: Perception is evolution’s gift—and its limit.

Epilogue: Embracing the Poetry of Perception

Though purple lacks a single-wavelength anchor, it vividly colors our emotions—from Van Gogh’s swirling purple in Starry Night to the proud purple of the LGBTQ+ flag, or the melancholic “blue-purple” of blues. It proves: The world isn’t just light’s objective projection; it’s the brain’s creative theater. The next experiment might unlock more “non-existent” colors. What do you think? Share your “purple story” in the comments—is it romance, or melancholy?

Further Reading: The Ice “Superpower” Awakens: Flexoelectricity in Ice Unlocks New Clues to the Origin of Lightning